There’s a reason the phrase ‘the personal is political’ has found its way into almost every important social justice movement of our time. Though that phrase has come to mean something different to every generation, it still serves as a powerful slogan for underrepresented populations, whose stories are often lost amid the clamoring politics of the privileged. In order for there to be real change, we need to hear those stories—we need to hear their voices.

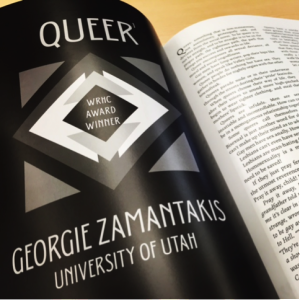

This year, Scribendi magazine had the pleasure of publishing Georgie Zamantakis’ essay, entitled “Queer1.” The footnote for the title of the essay reads: “These are the words I have been witness to as a transfeminine, rural queer living in Utah,” and I share that with you because of its importance to this essay, which was also the winner of the WRHC (the Western Regional Honors Council) award for Creative Nonfiction.

“Queer1” is a tough read at times, I’m not going to lie; hatefulness and bigotry are never pleasant to witness. In this essay, Zamantakis takes all too familiar stereotypes alleged against the LGBTQ community, and blends them with their own personal experience growing up queer. The result, a brutally honest representation, is nothing short of unique—which is deeply ironic considering the pervasiveness of many of these stereotypes, and the unfortunate similarities in experience for many other people identifying as queer: Zamantakis has appropriated the speech of the disapproving majority and carved their own voice over, emerging in the process the voices of countless other people struggling to be heard.

In this candid interview with Scribendi, Zamantakis expands on their intentions when writing this piece, and shares more about themselves, their writing process and their politics.

Sarah Haak

INTERVIEWER

How does it feel to get published and win this award?

ZAMANTAKIS

It feels amazing to get published and to win this award. This is the first time I’ve been published, and for me, this is more than just having my writing recognized. This piece is a reflection of the pain others have caused me through their homophobia and their transphobia, as well as a celebration of the way being queer* has strengthened and transformed me. Having this piece published means having these pieces of my history and my story honored within the academy. Too many times, on the streets, in my home, and in school, I have been told that I am too weak, too passionate, too femme, and too illogical. This piece pushes back against that hatred and degradation and the publishing of it proves that this femme is powerful enough to fight back and make it.

INTERVIEWER

What made you sit down and write this piece?

ZAMANTAKIS

I wrote this piece for an Honors writing course as an assignment. We were told to write a creative nonfiction essay based off another piece we had read. We had read a piece, which was basically a collection of outrageously ignorant statements individuals had made about India throughout time. I don’t think there’s a purpose in doing work or going to school if it in some way doesn’t stem from everything that is important to me, and being queer is critical to my being. I decided to write a piece that mirroring the other through which I was able to capture the pain I felt growing up and to heal through writing about it.

INTERVIEWER

Can you tell us a little about yourself?

ZAMANTAKIS

I’m from Helper, Utah, a small, coal-mining town in Central Utah. I was born and raised in this town, and growing up there was often difficult and violent as a queer, gender-nonconforming individual. As soon as I could, I ran away to Salt Lake City for school and never considered returning. I was taught that the urban landscape would offer me refuge, but I’ve since learned that’s false, and after years of healing and processing, I’ve begun to find power in where I’m from. Rural spaces are often seen as spaces of ignorance and hostility, but I think a lot of the “backwardsness” that gets associated with rural spaces stems from classist ideologies. Urban spaces have been no safer for me than the rural, they have only offered me more resources.

I’m currently in my third year of school at the University of Utah, studying Sociology and Gender Studies. I’m hoping to either get my Ph.D. in Sociology or Education, Culture, and Society and to teach Sociology and Gender Studies at a community college somewhere. I also hope to return to the rural landscape one day to reclaim the magic and power of what it has to offer.

In my spare time, I enjoy eating vegan Thai food, connecting with others and building family, finding love, and reading books, watching shows, and listening to music that push me in my work as an activist.

INTERVIEWER

Do you read much and if so who are your favorite authors. What book/s are you reading at present?

ZAMANTAKIS

I try to read as often as I can. Some of my favorite authors include Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Gloria Anzaldúa, Audre Lorde, and bell hooks. I’m currently reading Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, a biomythography by Audre Lorde.

INTERVIEWER

If you had to choose, which writer would you consider a mentor?

ZAMANTAKIS

I don’t think I could choose one author as a mentor or an inspiration. I’m inspired by the multitude of works written by femmes of color, queer femmes of color, and trans* femmes of color. The strength, love, power, reflection, and ferocity of everything I read by people such as Audre Lorde or Janet Mock or Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie fill me, heal me, and push me in my writing and my work as an activist. Writing, to me, isn’t just something to do to pass the time. Writing is what I do to heal in a world that does not love me or find me beautiful. Writing is what I do to reclaim my power as a queer, transfeminine individual in a brutal world. Writing is what I do to find myself within my queer and trans* ancestry. All of these femmes show me what it means to lay claim to oneself wholly and entirely and to write for oneself and for one’s community. I do not write for straight, cisgender people. I write for other queer and trans* folks, and most importantly, I write for myself.

INTERVIEWER

Can you tell us a little about your writing process?

ZAMANTAKIS

When I write, I try to carry all of me with me and to fill my piece with it. At times, I am angry. At times, I am sad. At times, I am overflowing with joy. And in all of these moments, I write to capture these affects. I think about what words and what stories will bring healing for me. I consider how representative this story is of me and others and those who I am forgetting. I reread the piece not to check for spelling errors but to see whether I have accurately depicted who I am in the piece or if I have written something I am not.

INTERVIEWER

What is the best advice you’ve ever received as a writer? What advice would you give to other writers?

ZAMANTAKIS

The best advice I’ve received as a writer, as an activist, and as a person is to do this work for me. It’s difficult for me to disconnect the pieces of myself and consider advice that only applied to writing. However, as a transfeminine individual, I dress, identify, and live the way I do for me. I don’t exist for others, and I don’t write for others. I write for myself: to find myself, to heal myself, to free myself, and if others are able to connect with that, then that’s transformative for both of us. But in a world that has taught so many of us to be and do in ways that comfort others, I see no better advice than to be and do for me.

INTERVIEWER

Is there anything you would like your readers to walk away with after reading “Queer”?

ZAMANTAKIS

I’d like other queer and trans* folks in rural spaces to be able to read it, to maybe connect with it, and to be able to heal through it as well. I’d like for straight, cisgender folks to read it and leave feeling the pain and discomfort I’ve felt throughout my life, and to begin interrogating their own actions, beliefs, and identities to critically examine how they can create spaces that honor queer and trans* identities.